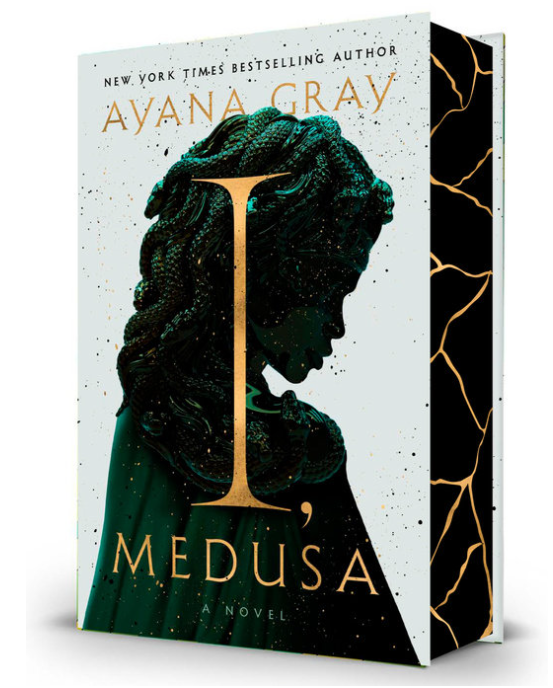

I just tore through Ayana Gray’s I, Medusa in a single sitting, and I’m still holding onto its ethos. This is a mythological origin story turned inside out, one that reclaims Medusa not as the monster of legend, but as a girl, a sister, a priestess, and someone who eventually becomes powerful, dangerous, and deeply, tragically human. If you liked the Velaryons in Game of Thrones, their sea-steeped nobility, their tangled loyalties, their family politics, you’ll feel the same undertow here in the portrayal of Medusa’s lineage and the weight of her origins.

Here Medusa herself is raw and real, her longing and her fury fully fleshed out. She’s naïve, reckless, brave, grieving , a girl who wants to belong, even when the world is determined to exile her.

Some of the most fascinating characters for me were not just Medusa’s sisters but her mother and Poseidon’s wife. Both are women caught in impossible positions, bound by duty, divine politics, and betrayal. Gray sketches them as more than archetypes, hinting at rich backstories. Medusa’s mother carries the grief of heritage and the fear of losing her children to powers beyond her control. Poseidon’s wife simmers with quiet strength, her presence suggesting not just rivalry but an entire shadow-story of what it means to be tethered to a god who takes what he wants in a society where that is the norm. Their stories felt like doorways into whole novels of their own, and I found myself craving more of them.

The islands, temples, markets, and the salty press of the sea are richly drawn, immersing you in a rose oil and rosemary-scented world that feels both ancient and immediate.

You know how sometimes when you enjoy something, you want to dig deeper? The book does address a lot: betrayal, abuse, agency. But sometimes I felt it danced along the edges when it could have plunged in: exploring the weight of being visible (or invisible), the internal conflict between mercy and vengeance, sisterhood under pressure, the cost to one’s self in reclaiming power. The mothers, wives, and sisters here embody centuries of silenced voices. I wanted the novel to dive deeper into their shared burden, to show more clearly how women navigate survival in a world run by gods who treat them as pawns. There are hints of so much more, but not always enough space to explore them fully.

Medusa’s shift into the “monster” is compelling, but I sometimes wished for more inner wrestling. Not just how others see her, but how she sees herself: the horror, the liberation, and the possibility of reclaiming that identity on her own terms.

Final thoughts

Even with these gaps, I, Medusa is a triumph: a reclamation, a fierce retelling, and a deeply human portrait of a girl on the cusp of myth. The version of Medusa that I grew up with and has stayed with me is the one slain by Perseus in Clash of the Titans (1981). It is only recently, earlier this year actually that I delved into her backstory and learned that she was once a maiden, enraged by her rape, blamed and demonized by society. I turned the final page with sadness, not because the story disappointed, but because I wanted to linger longer with these characters especially the women standing just beyond the spotlight.

Medusa’s mother and Poseidon’s wife hint at whole epics of resilience and rage we may never read, and that absence is its own haunting. Medusa’s myth feel raw and urgent. It’s heartbreaking. It’s enraging. It’s hopeful. If you’re craving mythology retold, if you want villains who are more than villainous, or if you want stories that make you reflect on what legacy means: this is for you. I only wish some parts went a little darker, a little deeper, less sanitized especially through the feminine lens. But maybe that’s part of what makes this version so human: it refuses to be all monster, even when she is becoming one.

Note: Thanks to Netgalley and Penguin Random House for the opportunity to do an early review of this reimagined fairy tale.